He will open your eyes. Or rather, he won’t as much as open as he will show you where to look.

“Ol’ pirates yes they rob I, sold I to the merchant ships, minutes after they took I, from the bottomless pit, but my hand was made strong, by the hand of almighty, we forward in this generation…triumphantly.”

We break into song during our interview because that is who he is.

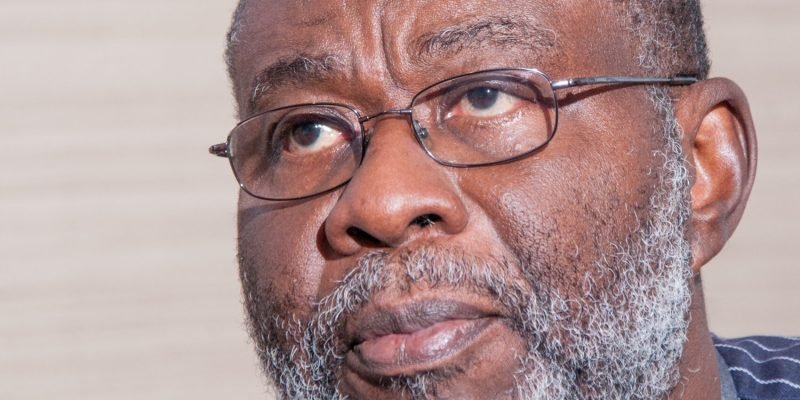

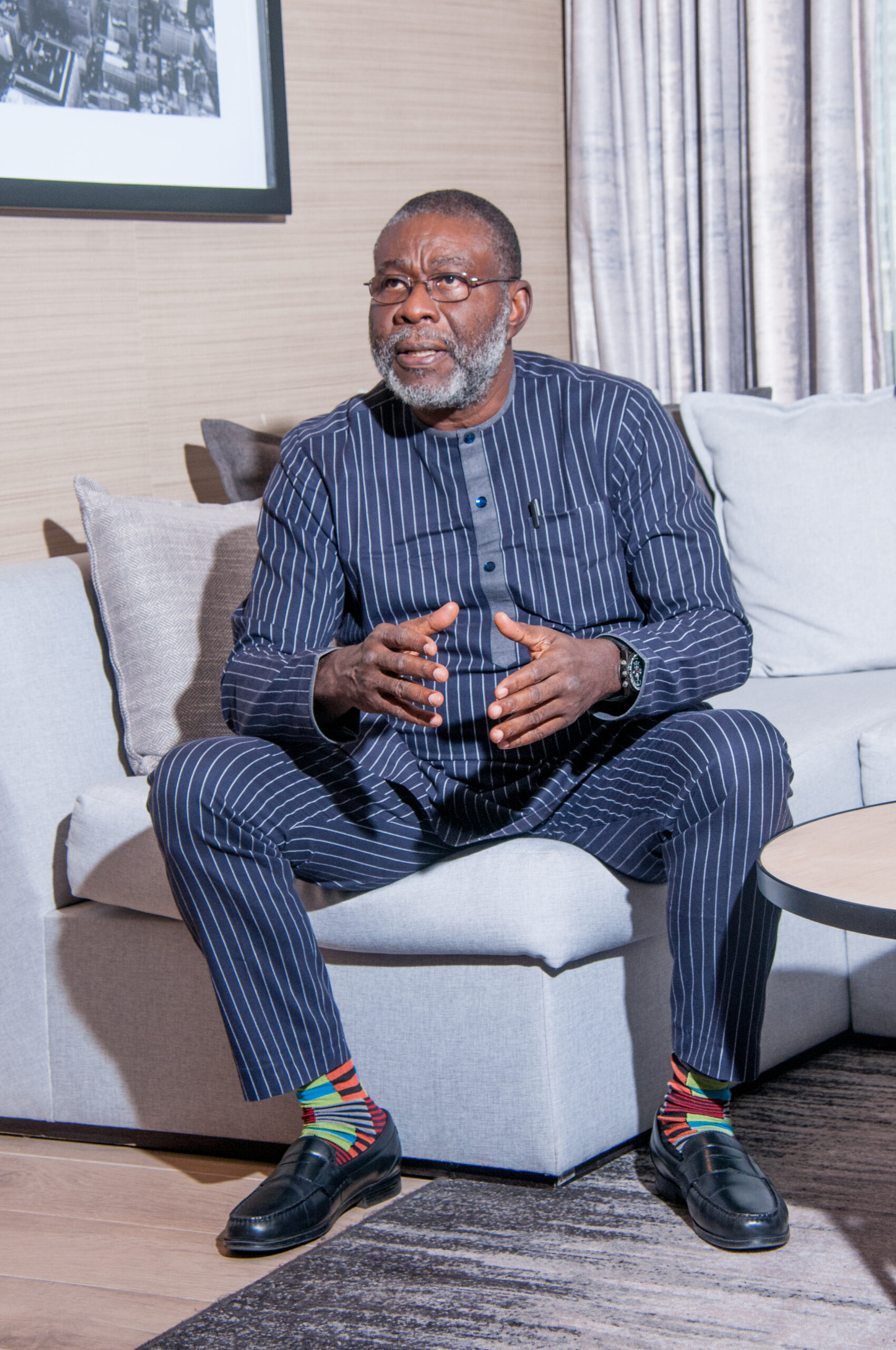

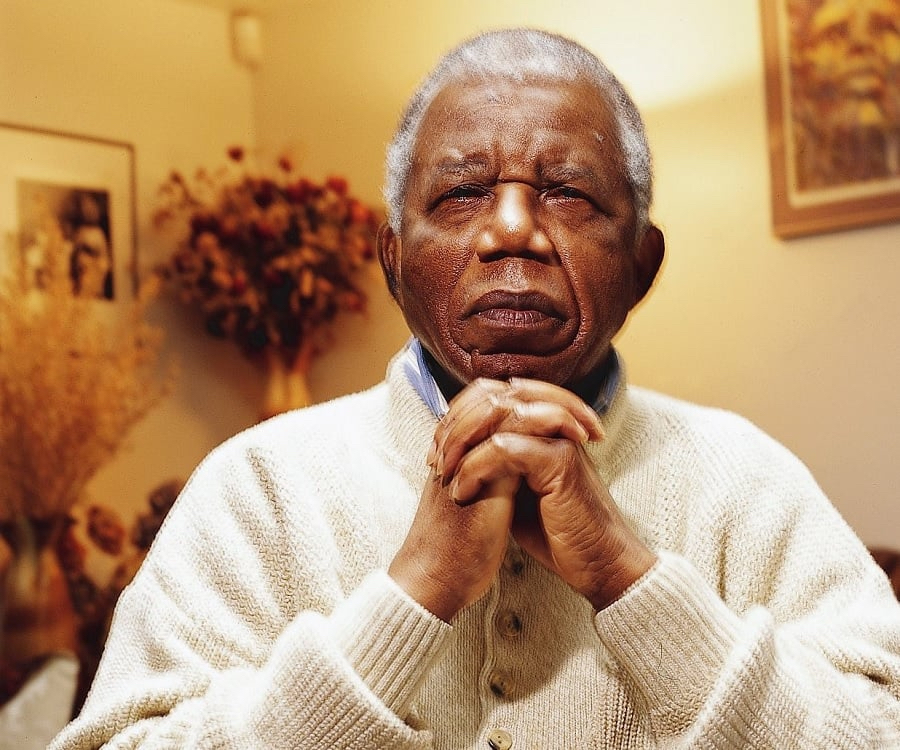

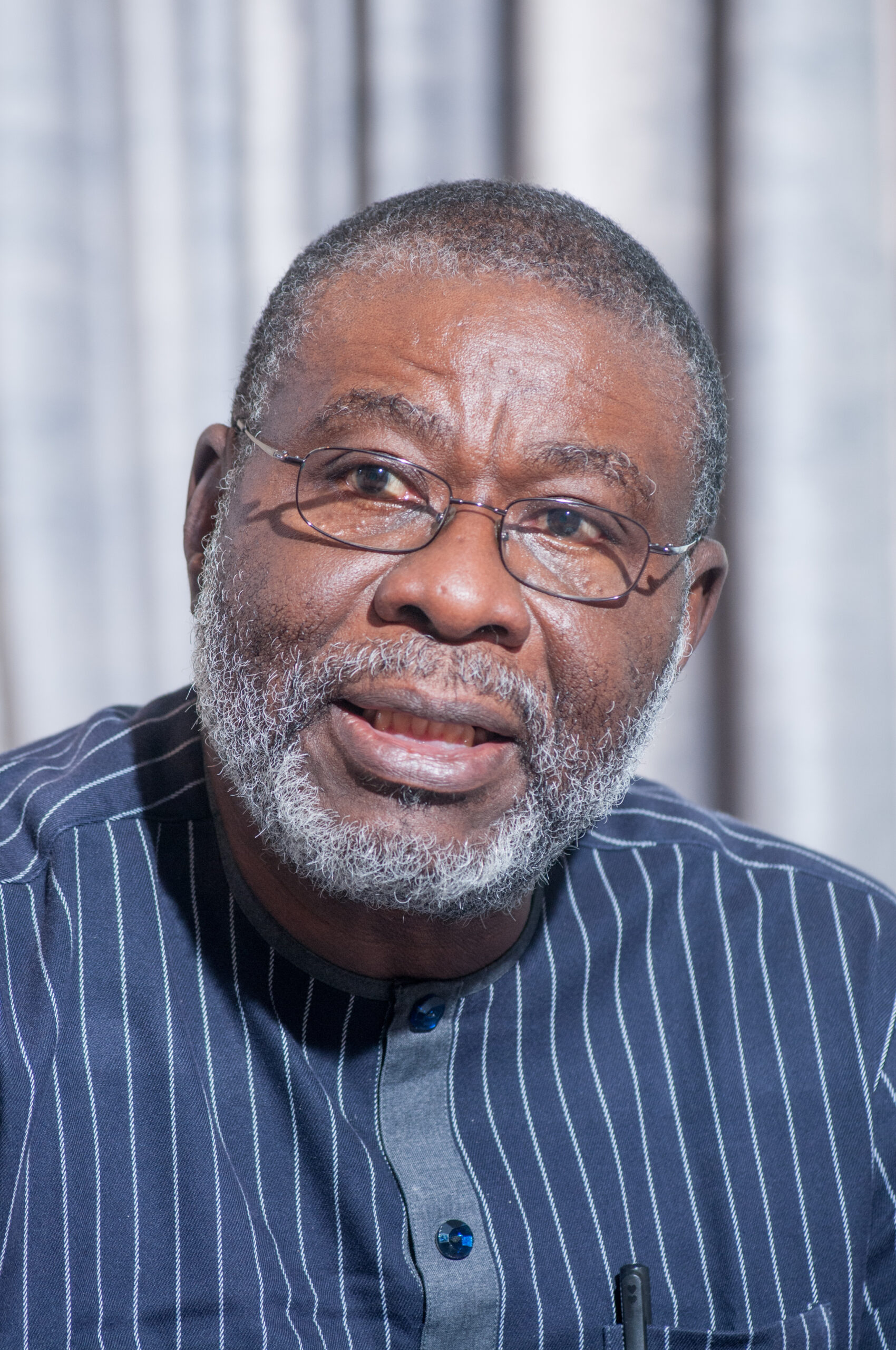

He has the regal bearing of an emperor, with the elegant mane of gray hair and wise golden eyes, and smelled like mint aftershave and old books.

He who tells stories with the cautious delight of a gossip. He who is not afraid to bare his soul and, in so doing, makes me bear mine.

I want to tell him things, but I want to listen to him too. I need more ears.

“We must create a new roadmap for Africa within the context of climate change and development and security.”

Two are not enough to lap up all his words; I am conflicted, I am intrigued, I am challenged, I am subdued, I am encouraged, I am…I am.”

He is like actual content between the thousands of ads.

The day we meet, he is wearing a pair of black, khaki trousers, a checked shirt, and the chef’s kiss — a denim jacket that slices off about seven years from his age.

He looked very handsome in a professorial way.

We are supposed to talk about climate change, security and development in Africa, but wait…

“In Africa, our challenges are not technical, they are adaptive, but we insist on technicalities because it is what we know, what is easy.”

He has the regal bearing of an emperor, with the elegant mane of gray hair and wise golden eyes, and smelled like mint aftershave and old books.

Life has been his best college, and climate and security are his Harvard.

He scrutinizes the area with the ambition of an architect before letting loose like a twenty-something-year-old chasing the next high and spending money like it is going out of fashion.

“Over time and experience, I have come to understand I am here bound by a particular happenstance. I am here for a reason, and there is a reason why I am here.”

He is Olatunji Lardner Jr.

Fold your hands; the professor is in town.

How to define him, then?

To define is to limit, but I didn’t get this far for want of trying.

A TED Fellow.

A Reuter Scholar/Knight Fellow at Stanford University (1988-9).

A former journalist (as if you can ever be a former journalist). Media and communications expert, having managed complex communications advisory services across various countries, including Nigeria.

He is also the founder of WANGONeT, the first civic technology initiative in West Africa.

Crucially, he is a foundational member of the Savannah Centre for Diplomacy, Democracy and Development where he is shaping its security and development programs.

Presently, he is the chief executive of the Police Reform and Transformation Office (PORTO) — the special service delivery unit that he helped set up, the coda to his glittering career.

He is a human CPU. A linguistic Rubik’s Cube. A verbal PlayStation. He is a father, and—well, I didn’t do it justice.

Maybe he should speak for himself.

Really, it’s a proverb at this point.

Tunji does what only Tunji can do.

Tunji then can only speak for and on behalf of Tunji.

What is it the Holy Book says? “The words of a whisperer are like delicious morsels.”

What is it like then to be him?

Tunji speaks in schpritz, a drop will come your way in the end that you might relate to or understand, but in the meantime, you’ll have to listen patiently.

“Being me is a profound question. If you are schizophrenic like me, the three of us, me, myself, and I. I have realized that, in the grand scheme of things, I am statistically irrelevant. And that leads to the realization that there is a reason I am here.

“The third thing is how do I begin to manifest that reason that has conspired to make it possible for me to be here. Those three conflate into a sense of identity that supposes that the reason why I am there is because I am here for a reason.”

Tunji speaks in schpritz, a drop will come your way in the end that you might relate to, or understand, but in the meantime, you’ll have to listen patiently.

He is a highly-tuned philosophia with Zen-like mind control and the craftiness of a fox on the hunt.

“As a matter of fact, we are saving ourselves from ourselves. That’s how I view climate change — because man can affect the planet at unprecedented levels. We are now the causalities of climate change.”

When he talks back at his life, so much of it seems to have been fated.

For instance, I have heard a lot of stories about boys, but only one of a boy who had such an insatiable appetite for knowledge, especially knowledge that has no bearing on anything.

No, not knowledge for knowledge’s sake, but knowledge for knowledge’s sake.

“You can say I am a philosopher — ‘philosophia’ after all is a lover of wisdom. Why do we have all this wisdom? It is almost an etymological question: why me?

“Over time and experience, I have come to understand I am here bound by a particular happenstance. I am here for a reason, and there is a reason why I am here.”

Living in a VUCA—volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity —world, and one that is built on categorical distinctions of Us vs. Them, Speculative vs. Mimetic, Linear vs. Non-linear — Tunji somehow is a generalist and specialist.

The challenge is to make sense of the VUCA world; that is what informs my perspective, he says.

Crucially, he is a foundational member of the Savannah Centre for Diplomacy, Democracy and Development where he is shaping its security and development programs.

“We are coming to a point where there is almost a singularity, but we can make sense by approaching it with a sense of intellectual modesty. The space between causality and the effects can be so long that you cannot effectively trace its origin such that you mistake the effect to be the cause.”

Many years ago, he says, the conversation was about saving the whales. Then it became about saving yourself.

“Go back to the indigenous wisdom sets instead of these filtered conversations by colonialism, westernization et al. First, you have to learn, then unlearn, then relearn.”

“As a matter of fact, we are saving ourselves from ourselves. That’s how I view climate change — because man can affect the planet at unprecedented levels. We are now the causalities of climate change.

“I have looked at it from my life experience and inevitably concluded that we are screwed. How can we work together to change this? Well, how can we? There is a saying in Africa that no matter how far a man urinates, the last drop will always fall at his feet.”

Suggestive image aside, Tunji drops the bombshell.

“People have to accept a semblance of responsibility for their agency. They often deflect or outsource it to some other agency; typically, it is God. And I do not mean this in a religious way. It is compounded mentality — learned helplessness.

“Oh, why me? Through your contribution or lack thereof, you are willingly creating your future. It’s not the circumstance that is important; it is your awareness of said circumstance. Sometimes in life, it is not the thing itself but how you look at it.”

“You get good security by having good governance and good governments. Humans want to live their lives, eat their food, and have their families with a sense of security and peace.”

He coopts a phrase from Canadian communication theorist Marshall McLuhan who says the medium is the message.

“Sometimes the distance is so far you forget the causalities. Our job is to remind them.”

But how?

“The trickle-down medium is tricky because it supposes I have the responsibility. What about you? With all your God-given humanity, why don’t you want to see it? Learned helplessness, I charge it to you. ‘If only they can,’ ‘if only they will,’ but what about you?

“Go back to the indigenous wisdom sets instead of these filtered conversations by colonialism, westernization et al. First, you have to learn, then unlearn, then relearn.”

Listening to Tunji, you will not miss the unmistakable whiff of bombast and maximalist self-fashioning.

Forgiving the tiny exaggeration there, it is true that being in the room with him carries some force, such force that you are either converted or challenged.

Sometimes converted and challenged such that we might position Tunji in his proper place in the pantheon of history’s contemplative curmudgeons.

That’s why it will not shake the earth from its axis to learn that he spent a lot of time reading and learning and owes that to his father.

“My daughter tells me I never infantilized her. I treated her as a fully-fledged adult, mindful of certain limitations because she was still a child anyway.”

“You have to be curious, and that curiosity expands your mind, which leads you to conventional school knowledge. Albert Einstein says education is what remains after you have forgotten what you learned in school.”

The relearning part is almost a cosmic experience, he says. This is where I have to rearrange my little cosmology on life and the planets.

It is not necessarily linear; you learn, unlearn and relearn. It is how he grew up.

It is how he sets up a shrine for the gods of his childhood in his adulthood.

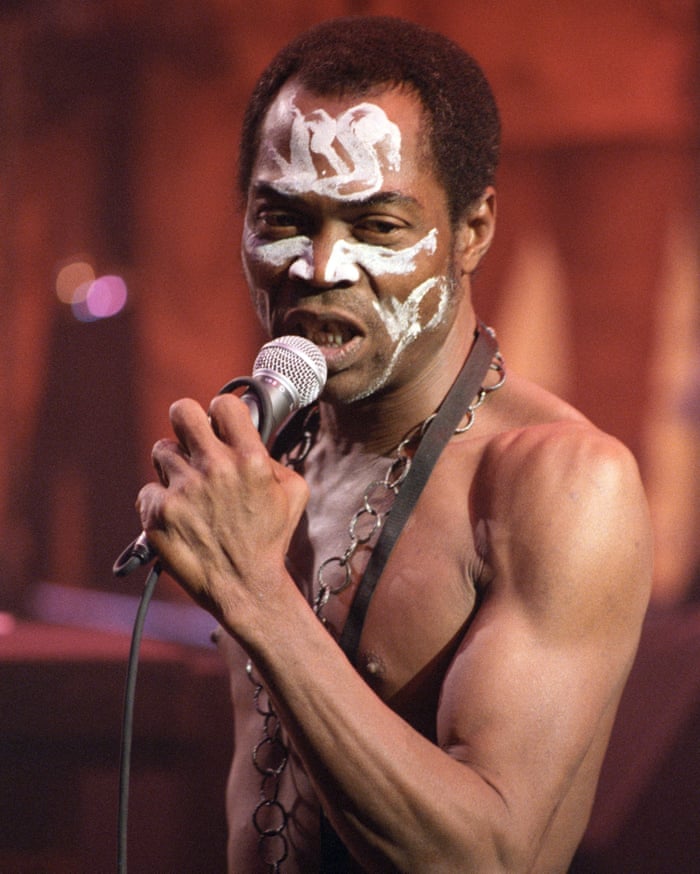

Like how he talks fondly of his father. How close they were. How they were friends with Fela Kuti, and how he grew up listening to Fela.

How such a dude his father was, and how he learned to offer compassion.

How he truly loved his son, Tunji Jr — him.

“Security is development, and development is security. You cannot divorce issues of development without factoring in security.”

And how he one day almost got him thrown into prison because Tunji Jr had written an article and he — Tunji Jr — had not adopted the ‘jr’ part of the name yet, and three men wearing suits wanted to throw a certain Tunji in prison, but this old man, this Tunji Sr, did not look like much of a writer.

To save Tunji Sr from ‘mistaken identity,’ Tunji added the ‘jr’ to his name. Olatunji Lardner Jr.

“My dad said I never accepted anything at facial value, not even his dad-ship; he had to justify it. My acceptance was bound by convention and not necessarily agreement. He had to justify it.”

Now a father of two, he has seen his children grow up to give him as good as he gave.

His son is eternally curious. His daughter, ever the questioner.

“A lot of challenges we are having, including the Boko Haram, is majorly due to climate change.”

“My daughter tells me I never infantilized her. I treated her as a fully-fledged adult, mindful of certain limitations because she was still a child anyway. And, of course, her wit is vicious, even more than mine.”

The question then is, is the goal of questioning to question or to get answers?

“You are talking to a philosopher. The goal is to ask more questions because the answers invariably lead to more questions.”

When you are young, he says, you have a lot of moral absolutism.

The older one gets, the more you discover much more to the world than your monochromatic view.

Now, Tunji is writing a book where he reminisces on the moral absolutism of his youth.

What has remained steadfast has been his perpetual insistence on finding the reason for being here after all.

“In Africa, the past is never dead; it is not even the past.”

“My life is about synchronicity. I have to be in sync with the universe. What is your own higher purpose in life? I am at the phase I am unlearning what I knew about science before, where I was caught up in a Western rationalist mindset that objectifies the rational process as the only way of looking at science, yet we still have the subjective reality of culture, which is how we Africans look at it. I have only adopted the English language because you seek to convert a man by his religion.”

It is in seeking to convert the said man that he is in Nairobi for a security and climate change conference — The First African Edition of the Berlin Climate and Security Conference, held in Africa.

Yes, the irony is not lost on him either.

“As an African, you are simultaneously living your life in the past, the compounded present, and the potential future.

“A lot of challenges we are having, including the Boko Haram, is majorly due to climate change. People just want to survive. Security and climate change, there is a nexus there.

“The microcosm reflects the macrocosm and vice versa. It is a mirror and refracted image. Security is development, and development is security. You cannot divorce issues of development without factoring in security.

“You get good security by having good governance and good governments. Humans just want to live their lives, eat their food and have their families with a sense of security and peace.

“Chinua Achebe surmised it perfectly: The trouble with Nigeria is simply and squarely a failure of leadership.”

Tunji spices it up. “The colonial mindset is a gift that keeps giving —even the police are not the police’s friend. My task is to change the narrative from a police force to a police service.

“In Africa, our challenges are not technical, they are adaptive, but we insist on technicalities because it is what we know, what is easy.”

He says you can’t solve a problem thinking at the level at which that problem was created.

“We are now in the era of AI, and look how it has rendered the previous knowledge-based model irrelevant. These language models are being trained on Western ideologies, leading to an inherent bias.

“Our reality is not factored in — forgetting Africa is the archetype of homo sapiens. We have to introduce our reality, aware of the fact that presently AI is still supply-led rather than demand-driven.”

“We have wisdom. The West has knowledge.”

That is his rallying cry. Wisdom, he says, is a rung higher than knowledge. Our ancestors knew. Bob Marley knew. Tunji knows.

“Emancipate yourself from mental slavery, none but ourselves can free our minds, have no fear for atomic energy, cause none of them can stop the time…”

It is hard not to see the weight of the world bearing down on a single soul.

Tunji wants you to question anything. Everything. Ratiocinate.

“What does sustainable development mean? It means different things to different people. In 2017/18, I spent a four-month sabbatical at Indianapolis University, talking about development space and technological advancements.

“One of the fundamental lessons I learned is you cannot be too far ahead of the people you lead. You have to be patient, which is a visionary leader’s responsibility. Reality is not binary. It is and/and, not either/or.”

He wrote an essay, Africa’s Time Conflation Challenge, arguing that we know about the past and the present, and the dialectics is that past issues are always present.

“An African man lives his life both in the past and the present, yet he is quick to calm the waters.”

He buttressed this argument by quoting William Faulkner, “In Africa, the past is never dead, it is not even the past.”

“As an African, you are simultaneously living your life in the past, the compounded present, and the potential future. For Africans, the past is integral to our understanding of time. Ergo, all the colonial and early post-colonial challenges of African states, such as the supremacy of Western education to the detriment of indigenous knowledge, division of society into native (rural) and civic (urban) areas, tribalism, and military intervention in politics, are still recurrent African challenges in the 21st century.

“This means that an African man lives his life simultaneously in the past and the present.”

And yet, he is quick to calm the waters; there is hope.

The 22nd century belongs to Africa, he says, but you have to understand that mindset thing that it is possible.

That’s why he is at the Savannah Centre. It is where he will domesticate and Africanise the Berlin Conference so that we have something that ‘reflects our reality in all its ponderous and wondrous glory.’

“We have to create a new roadmap for Africa within the context of climate change and development and security. We also have to push back against the gaslighting of the West. We have to speak truth to power. We have to learn, unlearn and relearn our realities.”

Important, though, and how he views the world from his microscope, is that he is not wallowing; he is merely an observer, chuckling at mortality.

Good advice is like a nutrient-rich broth made from boiling down the bones of life.

He stays grounded in the arbitrary and unfair nature of things, like how he can be having a great time having a beer in Nairobi, and then a call comes in from the village, and he enters a different time zone, dealing with the realities of village life.

Reality does not incapacitate him. Instead, it merely amuses him. Because he has lived a lot, he has learned a lot and keeps learning, reviewing, and questioning.

What is something he long believed to be true but realized is not?

“I thought the world was binary. It is not. I believe we are in the quantum age right now. AI is here. It is the present. As an African, I used to think about linear time, now I think about time conflation, not time dilation. I am learning to appraise the world anew.

I know I am statistically irrelevant, he says. And The Buddha says that true wisdom humbles. If people have regarded you as an intellectual, or as a mystic, and a wise person, but you know that deep down, you don’t know anything. But I am African, so by definition, I am a wise man.”

In his seminal essay, The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus cites absurdity as a symptom of modern spiritual discomfort, where in a sympathetic analysis of contemporary nihilism and touching on the nature of the absurd, he prods the dissonance that occurs when man attempts to impose his need for rationality on the random structure of reality.

To Camus, there was only one way to liberate yourself from existential worry: by staying the course and following the absurd through to its logical conclusion.

Because he has lived a lot, he has learned a lot and keeps learning, reviewing, and questioning.

In other words, learn to embrace, or at least tolerate, the sheer weirdness of your existence, and you will have a much easier go of things. Olatunji Jr, it seems, is as assured of life’s meaninglessness as he is of its value.

“I wish I said more often that love is the greatest organizing principle in the universe. Once you understand that, alongside a quote by my favorite scientist, Nikolai Tesla: To understand the universe, you have to understand three things: Energy, frequency, and vibration. Love is the greatest organizing principle in the world. This came to me yesterday.

“Once you understand these four things, you are well on your way to paying your rent on earth.”

What’s love to him?

“I don’t do romantic love. I do agape love which is self-giving, not self-seeking. That’s why you are here, my brother.”

Is the philosopher happy?

“All things considered, I’m good. I am happy as a statistically irrelevant human in a VUCA world.”

Good advice is like a nutrient-rich broth made from boiling down the bones of life.

Here, Olatunji Lardner Jr has handed the world a cup.

As I head home, Bob Marley plays and hums and croons in my brain.

“Oh, won’t you help to sing? These songs of freedom. Cause all I ever have…Redemption Songs.”